I just posted the following to my group blog for a program I am a part of through Princeton Theological Seminary. One of our assignments was to listen to the following podcast by Eboo Patel, and the following is what I wrote in response to what he had to say. Patel is a Muslim, and yet he promotes an inter-faith approach to things. As you will be able to infer from what I wrote in response, I don’t agree with him, even if I think his desires are noble (which I do think they are). Click here to listen to the podcast if you want (it is approx 18 minutes). Here is my response:

I just finished listening to the assigned podcast for pre-session #4 class work which was a short lecture given by Eboo Patel on interfaith interaction and ecumenical and inclusive engagement between various faith traditions; in particular, for him, between Christians, and his faith tradition, Islam. And yet as I listened to Patel’s very articulate and winsome talk, what stood out to me was that he seemed to be ameliorating the substantial differences and distinctives inherent between Islam, Christianity, and other ‘faith’ traditions. And that he places a higher premium on our shared human and earthly situation, and in the process diminishes the ‘eternal’ realities that give each of our faith traditions there actual distinctiveness; that is, I see Patel diminishing the significance and thus importance of what we think about God. It appears that Patel holds to the an idea that the concept ‘God’ is actually an ‘eternal’ reality, who in the end ends up being the same reality, and thus in the present what is important in the ‘earthly’ experience of ‘God’ is to focus on our shared experiences and various, but shared expressions of ‘faith.’

I just finished listening to the assigned podcast for pre-session #4 class work which was a short lecture given by Eboo Patel on interfaith interaction and ecumenical and inclusive engagement between various faith traditions; in particular, for him, between Christians, and his faith tradition, Islam. And yet as I listened to Patel’s very articulate and winsome talk, what stood out to me was that he seemed to be ameliorating the substantial differences and distinctives inherent between Islam, Christianity, and other ‘faith’ traditions. And that he places a higher premium on our shared human and earthly situation, and in the process diminishes the ‘eternal’ realities that give each of our faith traditions there actual distinctiveness; that is, I see Patel diminishing the significance and thus importance of what we think about God. It appears that Patel holds to the an idea that the concept ‘God’ is actually an ‘eternal’ reality, who in the end ends up being the same reality, and thus in the present what is important in the ‘earthly’ experience of ‘God’ is to focus on our shared experiences and various, but shared expressions of ‘faith.’

Interestingly, what Eboo Patel is doing, and the way he is emphasizing a ‘pluralistic’ approach to inter-faith cooperation sounds very similar to the way that theologian John Hick approached his expression and understanding of Christianity through his ‘pluralist universalist’ approach. Christian theologian Christian Kettler describes Hick’s approach (and quotes Hick in the process); notice, as you read this, how well Hick’s approach (as described by Kettler) dovetails with Patel’s approach. I think there is more than coincidence going on between Patel’s informing approach, and how Hick approaches things; here is Kettler on Hick:

Hick responds to this challenge by stressing 1) the structural continuity of religious experience with other spheres of reality, and 2) an openness to experimental confirmation. “Meaning” is the key concept which links religious and mundane experience. “Meaning” for Hick is seen in the difference which a particular conscious act makes for an individual. This, of course, is relative to any particular individual. Verification of this experience is eschatological because of the universal belief in all religions that the universe is in a process leading towards a state of perfection.

The epistemological basis for such an approach is found in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. Hick’s soteriology is based on “Kant’s broad theme, recognizing the mind’s own positive contribution to the character of its perceived environment,” which “has been massively confirmed as an empirical thesis by modern work in cognition and social psychology and in the sociology of knowledge.” The Kantian phenomena in this case are the varied experiences of religion. All have their obvious limitations in finite humanity, so none are absolutely true.

In contrast to Kant, however, Hick believes that the “noumenal” world is reached by the “phenomenal” world of religious experience. “The Eternal One” is “the divine noumenon” experienced in many different “phenomena.” So the divine can be experienced, but only under certain limitations faced by the phenomenal world. Many appropriate responses can be made to “the divine noumenon.” But these responses are as many as the different cultures and personalities which represent the world in which we live. Similar to Wittgenstein’s epistemology of “seeing-as,” Hick sees continuity between ordinary experience and religious experience which he calls “experiencing-as”.

The goal of all these religious experiences is the same, Hick contends: “the transformation of human existence from self-centeredness to Reality-centeredness.” This transformation cannot be restated to any one tradition.

When I meet a devout Jew, or Muslim, or Sikh, or Hindu, or Buddhist in whom the fruits of openness to the divine Reality are gloriously evident, I cannot realistically regard the Christian experience of the divine as authentic and their non-Christian experiences as inauthentic. [Kettler quoting: Hick, Problems of Religious Pluralism, 91.][1]

Even if Patel is not directly drawing from Hick’s pluralism (which I doubt that he is not), it becomes quite apparent how Patel’s ‘earthly’ vis-á-vis ‘eternal’ correlates with Hick’s appropriation of Kant’s ‘noumenal’ (which would be Patel’s ‘eternal’), and ‘phenomenal’ (which would be Patel’s ‘earthly’). What happens is that the actual reality of God is reduced to our shared human experience of what then becomes a kind of ‘mystical’ religious experience of God determined to be what it is by our disparate and various cultural, national, and ‘nurtural’ experiences. In other words, God and the ‘eternal’ becomes a captive of the human experience, and our phenomenal ‘earthly’ experiences becomes the absolutized end for what human flourishing and prosperity (peace) is all about.

Beyond this, Patel, towards the end of his talk uses a concept of ‘love’ that again becomes circumscribed by and abstracted to the ‘earthly’ human experience of that; as if the human experience of love has the capacity to define what love is apart from God’s life. But as Karl Barth has written in this regard:

God is He who in His Son Jesus Christ loves all His children, in His children all men, and in men His whole creation. God’s being is His loving. He is all that He is as the One who loves. All His perfections are the perfections of His love. Since our knowledge of God is grounded in His revelation in Jesus Christ and remains bound up with it, we cannot begin elsewhere—if we are now to consider and state in detail and in order who and what God is—than with the consideration of His love.[2]

In other words, for the Christian, our approach and understanding of ‘love’ cannot be reduced to a shared and pluralistic experience of that in the ‘earthly’ phenomenal realm. Genuine love for the Christian starts in our very conception of God which is not something deduced from our shared universal experience, but is something that is grounded in and given to us in God’s own particular Self-revelation in Jesus Christ.

In conclusion, I would argue that Eboo Patel’s ‘earthly’ pluralist approach is noble, but his approach is flawed because 1) ‘God’ cannot be adumbrated by our human experience (because for the Christian that our understanding of God is revealed from outside of us); and 2) ‘love’ is not simply an human experience that transcends all else, but instead is the fundamental reality of God’s Triune life. If love is the fundamental reality of who the Christian God is, then the object of our ‘faith’ as Christians, by definition, starts in a different place than all other religions and their various conceptions of God. If this is the case, then Christianity offers a particular (not universal) understanding and starting point to knowing God, and thus to understanding how love relates to truth (and vice versa). And yet, Christianity remains the most inclusive ‘religion’ in the world, because God loves all, and died for all of humanity; but this can only be appreciated as we start with the particular reality of God’s life in Jesus Christ.

None of what I just wrote means that we cannot work alongside or with other ‘faith’ traditions; it is just important, I think, to remember that who God is remains very important, and in fact distinguishes us one from the other. And that while we can and should befriend and conversate with other faith traditions, in the midst of this, we should not forget that there still is only one ‘way, truth, and life’ to the Father, and that way comes from God’s life himself, in his dearly beloved Son, Jesus Christ. If we don’t want to affirm what I just suggested, then what we will be left with is something like John Hick’s ‘anonymous Christians’ with the notion that all ways are ‘valid’ expressions towards the one God ‘out there’ somewhere.

Bobby, what is the problem for which Patel’s view (or for that matter, Hick’s) is offered as a solution and to whom is it offered? The incommensurability of religious worldviews is not self-evidently a problem.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on James’ Ramblings and commented:

Reblogging, not because I agree, but because I appreciate the author’s exploration of Hick, Kant, and Barth.

LikeLike

Bowman,

I didn’t think the incommensurability of world views was being addressed in my post so much, that seems to be an understood that allows me to write what I did. The problem is the relativization of them as if all are equal relativized by our own subjectivities.

LikeLike

Bobby, you do make sense. But we do not find several teams with charismatic coaches that could form a league if only they could agree to common rules, a commissioner, and an official airline. We find linebackers charging through rows of second violins who have locked arms to stomp grapes among the clowns under the circus tent of a desert caravan. And when it is suggested (yet again) that it would really be in everyone’s best interest to chill out, join hands, and agree that disembodied transcendence is the true essence of all religion, Gandhi is not the hero who comes to mind.

LikeLike

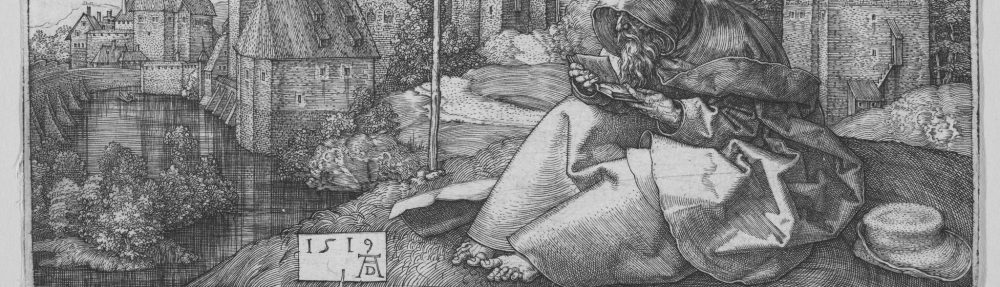

Oh, so you’re bothered by the picture I choose? I choose Ghandi because he represents just one of many available belief systems in our pluralistic age.

Patton? I’ll have to watch this later; I’ve watched it before in the actual movie.

LikeLike

Again, Bobby, Gandhi and all, your post makes sense.

Consider, however, Revelations, the Bhagavad Gita, the Tao Te Ching, the Heart Sutra, and Santeria ritual– how much common ground do they have for a comparison that is intelligible within them all? Is not the dream of such common ground an illusory ‘view from nowhere’? None of these belief systems are available to the uncommitted; availing oneself of any one of them renders the others more or less inaccessible. In practice, serious hermeneutical engagement across any one of these boundaries is very hard work that has never yet dissolved the boundary crossed.

And whose interests would be served by belief in such a universalizing ‘view’ were anyone to find it plausible? Is anything but Enlightenment mythology and the imperial power that depends on it threatened by candidly admitting that there is no super-discourse to which every actual ‘religion’ can be reduced?

If any argue that the metaphysical nightmare of disincarnate transcendence is the common ground on which we must engage, then we might suggest that, no, the dependence of every religion on its antecedents in time is the unavoidable ground on which we not only can make sense of religions, but in actual fact do make sense of them. Such a heuristic claims no special privilege for any religion, but it does deny all religions any right to flee from the known history of those before them.

LikeLike

Oh, yeah, I don’t disagree with you at all, Bowman … This is what helps to make pluralism so ironic as a concept; at least in its functional application.

LikeLike