Here at The Evangelical Calvinist we like to emphasize God’s grace, ‘all the way down’ as it were. We see this a necessary course correction given the imbalance that has been present, in particular, in the Western enclave of the church; since at least the mediaeval period, and working its way through Reformation and Post Reformation Western Europe and finally to the shores of the Americas  (North to be specific). I am sure, intelligent reader that you are, you know what I’m referring to; i.e. the impact, on the Protestant side (which is simply my focus here, we could also bring up the Roman Catholic roots of the Protestant past and present), that Post Reformed orthodox theology has had upon the development of what counts today as conservative evangelical theology (think, as a type The Gospel Coalition and the theology it distills for evangelical churches and pastors throughout the United States and beyond). We necessarily have been bequeathed a ‘legal’ faith which flows organically from the Covenant or Federal theology developed by the scholastics reformed in the 16th and 17th centuries. In other words, because of the ‘Covenantal’ framework defined by its two primary covenants, the Covenant of Works and the Covenant of Grace, Covenant theology starts its way into a God/world, God/humanity discussion from a soteriological perspective that is grounded in a relationship that is contingent upon a ‘mercantile’ or contractual understanding. And so what gets emphasized in this theology is a God who relates in a kind of “bilateral” way wherein he makes a pact (‘pactum’) with the elect where they will ostensibly live up to their end of God’s bargain by actuating the effectual faith they have been given, by God, in order to stay in good stead with God; a God who has made sure that all the ‘legal requirements’ of the broken covenant of works have been met by his sending of the Son, in Christ, fulfilling the righteous requirements of the covenant of works (i.e. the ‘law’), and thus instigating or establishing God’s covenant of grace. What happens here though is not an abandonment of a legal strain in God’s relationship between himself and humanity instead there is a reinforcement of that type of relationship; albeit it is now contingent upon Christ’s active obedience for the elect rather than on human beings without that type of grace. We could say more, but hopefully the gist has been felt.

(North to be specific). I am sure, intelligent reader that you are, you know what I’m referring to; i.e. the impact, on the Protestant side (which is simply my focus here, we could also bring up the Roman Catholic roots of the Protestant past and present), that Post Reformed orthodox theology has had upon the development of what counts today as conservative evangelical theology (think, as a type The Gospel Coalition and the theology it distills for evangelical churches and pastors throughout the United States and beyond). We necessarily have been bequeathed a ‘legal’ faith which flows organically from the Covenant or Federal theology developed by the scholastics reformed in the 16th and 17th centuries. In other words, because of the ‘Covenantal’ framework defined by its two primary covenants, the Covenant of Works and the Covenant of Grace, Covenant theology starts its way into a God/world, God/humanity discussion from a soteriological perspective that is grounded in a relationship that is contingent upon a ‘mercantile’ or contractual understanding. And so what gets emphasized in this theology is a God who relates in a kind of “bilateral” way wherein he makes a pact (‘pactum’) with the elect where they will ostensibly live up to their end of God’s bargain by actuating the effectual faith they have been given, by God, in order to stay in good stead with God; a God who has made sure that all the ‘legal requirements’ of the broken covenant of works have been met by his sending of the Son, in Christ, fulfilling the righteous requirements of the covenant of works (i.e. the ‘law’), and thus instigating or establishing God’s covenant of grace. What happens here though is not an abandonment of a legal strain in God’s relationship between himself and humanity instead there is a reinforcement of that type of relationship; albeit it is now contingent upon Christ’s active obedience for the elect rather than on human beings without that type of grace. We could say more, but hopefully the gist has been felt.

Laudably people like Brian Zahnd have been trying to come up against this type of ‘legally strained’ theology in an attempt to emphasize God’s grace and compassion apart from the forensics of it all. Unfortunately, as is often typical when we react, some things get lost in translation. In Zahnd et al. we almost end up with a type of antinomianism wherein the ‘legal’ aspects of Scripture’s teaching (now in contrast to the Covenantal framework) are completely vanquished from the picture; I don’t think this ought to be so. That said, we want to emphasize that God is gracious, and that his relationship to humanity is based upon His creative and first Word of grace; since this is what he has revealed to be the case in his Self exegesis in Jesus Christ. Karl Barth, of all people (can you believe it?!), offers an alternative and more balanced account (juxtaposed with Zahnd’s) when it comes to thinking about God’s relationship to humanity; when it comes to thinking about how God can still be thought of as someone who still has wrath and anger towards sin; and how that gets fleshed out in a radically Christ concentrated atonement theology. George Hunsinger helps us think about this in Barth’s theology, and he alerts us, along the way, to Barth’s own words on this:

2 The saving significance of Christ’s death cannot be adequately understood, Barth proposes, if legal or juridical considerations are allowed to take precedence over those that are more merciful or compassionate. Although God’s grace never occurs without judgment, nor God’s judgment without grace, in Jesus Christ it is always God’s grace, Barth believes, that is decisive. Therefore, although the traditional themes of punishment and penalty are not eliminated from Barth’s discourse about Christ’s death, they are displaced from being central or predominant.

The decisive thing is not that he has suffered what we ought to have suffered so that we do not have to suffer it, the destruction to which we have fallen victim by our guilt, and therefore the punishment which we deserve. This is true, of course. But it is true only as it derives from the decisive thing that in the suffering and death of Jesus Christ it has come to pass that in his own person he has made an end of us sinners and therefore of sin itself by going to death as the one who took our place as sinners. In his person he has delivered up us sinners and sin itself to destruction. (IV/1, p. 253)

The uncompromising judgment of God is seen in the suffering love of the cross. Because this judgment is uncompromising, the sinner is delivered up to the death and destruction which sin inevitably deserves. Yet because this judgment is carried out in the person of Jesus Christ, very God and very man, it is borne only to be removed and borne away. “In the deliverance of sinful man and sin itself to destruction, which he accomplished when he suffered our punishment, he has on the other side blocked the source of our destruction” (IV/1, p. 254). By taking our place as sinners before God, “he has seen to it that we do not have to suffer what we ought to suffer; he has removed the accusation and condemnation and perdition which had passed upon us; he has canceled their relevance to us; he has saved us from destruction and rescued us from eternal death” (IV/1, p. 254). The cross reveals an abyss of sin allowed up by the suffering of divine love.[1]

There’s something rather profound about this; we can still speak of God’s unrelenting judgment, it’s just that it is redirected in such a way that the focus comes to be on his desire to actually save us from our own self-destruction by giving us his own Self-vitality and eternal life in and through his Self-offering in Christ. The frame is one of eternal life and death; it is no longer about God meeting some sort of Self-imposed legal conditions so that he can have a relationship with his creatures.

I find this to be a much more winsome way, much more biblically and Christ-centered way to think about a God-world relation versus the one offered by Covenant theology and its covenantal schema of works/grace. In Barth’s alternative what’s at stake is not Penal Substitutionary atonement, but instead what Torrance calls an ‘ontological theory of the atonement.’ That is, the idea that reconciliation with God, i.e. salvation, is about pressing deep into the inner reaches of humanity’s real problem in relation to God; its problem with sin, and how that has plunged humanity into sub-humanity and living in a life of non-life and das Nichtige ‘nothingness.’ We see here in Barth, as we do so often with Thomas Torrance, the influence of St. Athanasius, and even an ‘Eastern’ understanding of what salvation entails in its most Christological senses.

God is still all about judging sin; he’s still wrathful and angry about sin; he still is all about righting the wrongs, and making the crooked straight; it’s just that, contra what I would contend is an artificial way to think about the Bible and God’s relation to the world in the Federal schema, the real issue is highlighted. The real problem with humanity’s plight is elevated to the level it should be at when we think about God and salvation; viz. what it means to be human before God. All of that is dealt with by Jesus, according to Barth [and Torrance] when God freely elects to become human in Christ for us, for the world.

I realize that those who are committed to Federal or classic Covenantal theology won’t have their minds changed by this; although they should. But I hope that for those of you with an open mind that this makes sense; that what God in Christ did, and is doing is not framed by a type of legalism (as it is in Federal theology – just go read some books on its history and development), but instead is framed by God’s gracious gift of eternal life for the world in himself, in Jesus Christ. And that because of this, because of who he is in this way for us, he graciously steps into our situation, and as the Judge becomes the judged. Has he met some sort of ad hoc legal conditions in this process; is that what he was ultimately about in reconciling the world to himself? Nein. Instead, he ‘elevated’ or exalted us to his position, by the grace of his life in the vicarious humanity of Christ, and recreated anew humanity in Jesus Christ. This is what salvation, and atonement was about; and it is out of this new eschatos humanity, Christ’s, where we participate daily in the triune life of God. This is the great salvation Paul tells Titus to be looking for; it is the one that was won in the incarnation and atonement of God in Christ.

[1] George Hunsinger,Disruptive Grace: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2000), 142-43.

Pingback: The Atonement of God in Christ: Covenant Theology, Penal Substitution, Ontology Atonement, Brian Zahnd, and Life Everlasting — The Evangelical Calvinist | Talmidimblogging

Couldn’t a legalist argue that God, by sending his son down to fulfill the demands of justice for us and in our place, has already forgiven us and reconciled himself to us even before the demands of justice were fulfilled on the cross?

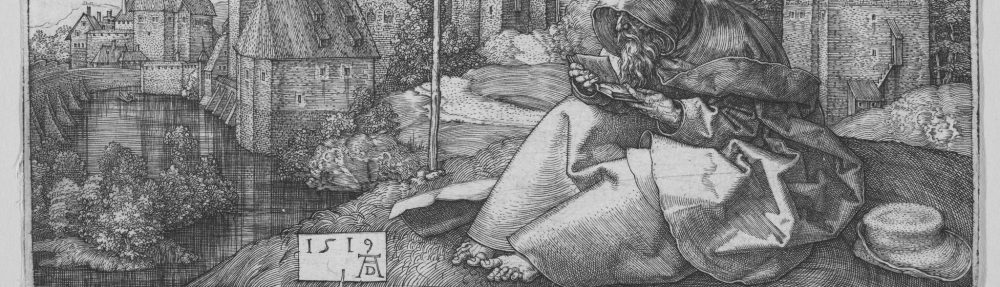

BTW, nice Chinese painting of Jesus’ crucifixion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ivan,

Are you asking, couldn’t they or would they? But no, they’d never argue that way; they work through Aristotle’s causations, and then they have antecedent, mediate, and executed will. All aspects need to be present in order for something to move from potential to actual.

LikeLike

Yeah I was asking couldn’t they, not wouldn’t they.

LikeLike

No, they couldn’t. Are you saying that because of the decretal system? Even so things still have to move from potential to actual.

LikeLike

I was not thinking in terms of the decretal system but in terms of God’s actual act of sending his Son.

LikeLike

So I’m not understanding your original question then. You asked why these guys couldn’t just say that people were forgiven apart from Jesus coming. On what basis are you asking that question then? It doesn’t follow from any theo-logic I’m aware of in the Federal system of thought.

LikeLike

Sorry for the late response. I have been busy for the past week.

What I was trying to ask was if federal theology, by stating that God does not forgive and reconcile himself to us until his standard of justice has been fulfilled through Christ taking on the punishment for sin, does not and cannot view the mere act of God becoming human in Christ as a sign that God has already forgiven and reconciled himself to us. In other words, is it the case that for the federal theologian, forgiveness and reconciliation does not take place until after Christ has taken on the punishment for sin and that before that single act, there is no forgiveness and reconciliation? I hope I made my question clear.

LikeLike

Oh, okay. Yes, that is what the Covenant Works/Grace matrix requires. It requires the active obedience of Christ on behalf of the elect; i.e. his fulfilling of the law both actively and passively (his death), and by so doing meeting the requirements and penalties that a holy God requires prior to his ability to actually love them and look upon them. This is what makes federal theology even that much more heinous when one considers what it does to the ‘who of God’.

LikeLike

I would need to read federal theologians myself.

So how exactly would justification fit into an ontological theory of the atonement is the focus of the atonement is about remaking human nature as opposed to a mere satisfaction of God’s law?

LikeLike

Sorry, that last sentence should have been read “if the focus of that view of the atonement”.

LikeLike

You don’t believe me? Lol

I’ve already written a gazillion posts on your question. You can go to my categories: salvation, atonement, vicarious humanity, and even Kevin Vanhoozer and you’ll find my answer about the ontological theory of the atonement. But just recently in some of my posts I’ve been responding to that question as well.

LikeLike